There is no equity without equity.

Nearly 125 years after DuBois’ quote, in 2021, blacks remain a poor race in an extremely wealthy country and world, and continue to bear the burden of what DuBois called “the Negro Problem” – or the feeling of poverty; cent-less, home-less, land-less, tool-less and savings-less, yet having to continuously enter into competition with “rich landed, skilled neighbors.” This is predominantly evident when analyzing the racial entrepreneurial landscape. Blacks remain a poor race and business class in America, during both economic expansions and contractions, even after more than a century-and-a-half of strivings.

A key factor in the ongoing lack of black wealth accumulation is the lack of capital in the black economic ecosystem. African-Americans, own the same proportional wealth in the United States in 2021 as they did in 1865, at the conclusion of 246 years of slavery. More specifically, the black community suffers from a lack of a foundational monetary system that helps determine the amount of capital that is invested in communities nationally and globally. Since blacks were among America’s and the world’s original sources of capital, they have been systematically designed out of the capital markets. This has been obvious by the way capital has flowed, or not flowed, to different racial communities – with blacks getting the least amount of capital.

Outside of capital invested in black forms of entertainment – such as professional sports and music – there is no equity risk capital in black America. With low levels of capital investment overall, primarily debt capital when it is available, and no risk capital invested into the autonomous minds of black children and young people, the entire equity of the black global diaspora remains underdeveloped. This reduces the aggregate confidence of both the black community from the development and execution of their own unique talents and gifts outside sports and music, and other communities. As a result, equity capital investment – the heart of wealth creation – is withheld and sparingly rationed to the black community, creating a vicious cycle of racial inequity.

Instead, capital is invested on behalf of black communities – usually into white-led intermediary efforts, organizations, and programs. In short, whites get equity capital and BIPOC, especially blacks, get programs. There is no hope of BIPOC racial equity without investments of financial equity into those individuals and communities.

What made Durham’s Historic Hayti the leading Black Wall Street in America was that it was built and sustained on a foundation of patient equity capital – Public-Purpose Private Capital. This led to its position as one of the most equitable socioeconomic ecosystems in America’s history.

The Current State of Racial Economic Equity

The challenge of addressing systematic structures of inequity are greater now than they were prior to the global spread of Covid-19 and the health-driven economic recession. Prior to the spread of the virus, economies were doing fairly well. “Racial equity investment” generally correlates to rising economies. A key to the success of any effort, and associated Theory of Change, is understanding the starting point of the problem that must be faced.

Part 1. RACIAL ECONOMIC EQUITY BY DESIGN: STAMPS ECOSYSTEM

The key to understanding how to change a system is understanding how that system starts, forms, evolves, and operates. Socioeconomic systems are both complex and adaptive. Complex adaptive social systems have distinguishing characteristics that help us understand them.

These characteristics comprise the fundamental properties of the socioeconomic ecosystem that we all currently exist in. These ecosystems designed, sometimes intentionally and sometimes unintentionally, and sometimes both, from their individual agents collective ambition and actions. In this model, these individuals can be thought of as “agent-entrepreneurs.” More precisely, they can be known as agent social entrepreneurs since their actions impact the design, development, functioning, evolution, and operations of society. These mostly autonomous agents fall into six disciplinary categories – the sciences, the technologies, the arts and humanities, the markets, the policies, and supports – or STAMPS for short. Most societies follow the general pattern of development.

This is the basis for the STAMPS Ecosystem.

part 1.1. RACIAL ECONOMIC EQUITY BY DESIGN: STAMPS ECOSYSTEM

America was formed as a STAMPS Ecosystem powered with the initial conditions of white, male supremacy. Two significant trigger points of this system was in 1619 with the arrival of the first black African slaves to America, and then again in 1776 with the founding of the country while still maintaining black slavery. Every component of the America way of life was built around racial inequity built into the STAMPS Ecosystem. As a result, every institution upbuilt by the majority agents included the same racist characteristics present at the beginning of the ecosystem. This led to institutional racism which anchored the White Supremacy STAMPS ecosystem.

Because of the economic growth and expansion of America based on the White Supremacy STAMPS Ecosystem Model it strengthened the same systems at the global level – which had been seeded with the same “lighter versus darker” racial inequities. These systems became embedded at the global level – especially in the economic systems – which have ultimately impacted every other system. Thus economic injustice is the forerunner to social injustice, criminal injustice, educational injustice, environmental injustice, and well-being writ large.

As a result of complex characteristics of social adaptive systems, the ecosystem has for 400 years fed on itself – influencing individuals, families, neighborhoods, communities, and institutions from the public, private, philanthropic, and academic sectors – across the entire STAMPS perspectives. This makes it incredibly hard to introduce new efforts at a scale large enough to alter the nature of the system – as it produces an endless array of innovative White Supremacy fractals.

part 1.2. RACIAL ECONOMIC EQUITY BY DESIGN: STAMPS ECOSYSTEM

The robustness of the White Supremacy STAMPS Ecosystem, and its complex adaptive nature over the last four centuries, offers us a glimpse into the true magnitude of the racial equity – as it is an ideological war that continues to rage today. This ecosystem outlives any one individual or generation, making it even more difficult to overcome.

Analogous to the current global fight against Covid-19, the vaccine response has got to be as grand as the virus. White supremacy is a virus as potent as Covid-19 and spread in much the same way – person to person, group to group, and from global community spread.

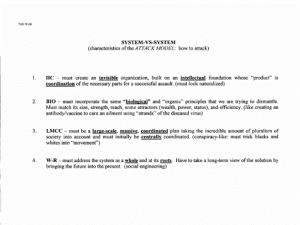

The vaccine to White Supremacy is Racial Equity. And the only way to spread it at scale is to design a Racial Equity STAMPS Ecosystem as effective and efficient as that of White Supremacy. Ultimately it is not individual project or initiative versus individual project or initiative. It is System versus System.

Part 2. RACIAL ECONOMIC EQUITY BY DESIGN: THE 5 C’S OF COMMUNITY ECONOMIC ECOSYSTEM UPBUILDING

Process-Oriented Community Economic Ecosystems

The concept of the business ecosystem is well-known. A business ecosystem is a network of organizations – including suppliers, distributors, customers, and competitors – involved in the delivery of a specific product or service through both competition and cooperation (Moore, 1993). The concept of a community economic ecosystem is a broader one than that of an entrepreneurship or business ecosystem. Whereas an entrepreneurial or business ecosystem is composed of networks of interacting firms, a community economic ecosystem is composed of networks of interacting individuals, families, homes, firms, organizations, institutions and entities. The community economic ecosystem includes greater interactions across a wider range of diverse and varied community members. In addition to the diversity and variety of interactions, the interactions are also different from those solely in business and entrepreneurial ecosystems. The interactions tend to be built around trust, mutual benefits, and a desire for collective achievements.

The Five C’s is the second leg of the Racial Economic Equity By Design Triangle Offense. The first leg, the STAMPS Ecosystem is a meta-level framework, seeking to understand how these broader systems of equity and inequity form and develop over time.

This second leg focuses on what it takes the agent social entrepreneurs to sustainably upbuild their community economic ecosystem. A central component of this work, is to ensure that racial equity is a founding characteristic of this work and part of the collective aspirations of the broader community. This model is relevant at all levels of community ecosystem building: micro, macro, and meta level – or local, national, and international.

Part 2. RACIAL ECONOMIC EQUITY BY DESIGN: THE 5 C’S OF COMMUNITY ECONOMIC ECOSYSTEM UPBUILDING

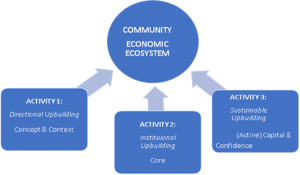

In Activity 1, directional upbuilding is driven by middlemen entrepreneurs. In this context, “entrepreneur” is not defined only as someone who starts a for profit business, but could involve an individual agent-worker involved in any number of efforts to support community upbuilding. In Activity 1, the middlemen group creates a community concept and assesses under what context they must function – or survive. Research emphasizes the importance of context, suggesting that each entrepreneurial ecosystem emerges under a unique set of conditions and circumstances (Isenberg, 2010). Each community economic ecosystem also emerges under a unique set of conditions and circumstances. Understanding the role of race as a contextual variable is critical to understanding how community economic ecosystems evolved in the past and the present.

In Activity 2, institutional upbuilding, the middlemen begin pursuing institutional upbuilding. This activity is the core of the process, and focuses on the types of entities that are established in a community. These are the categories and types of institutions that anchor strong community economic ecosystems. These categories may contain large and small firms, for profit and not-for-profit. These categories also serve to separate both the function and interests of the middlemen entrepreneurs, though there can be overlap.

In Activity 3, sustainable upbuilding, these middlemen determine the level of active community capital and confidence available and leverage that to begin upbuilding the community ecosystem in earnest. This activity understands “capital” to be a combination of five subcategories including community, experiential, financial, human and social. It understands “confidence” to include two kinds, internal and external, and measured by the belief that a community has in itself to succeed (internal), or the belief that an outside group has in that community to succeed (external). This confidence may be measured by the willingness to invest the aforementioned five forms of “capital” into the community’s concept (i.e., vision).

Since these capital and confidence levels are often low at the beginning of the upbuilding process, middlemen might have to begin the upbuilding process from a modest state. This means that the development process of a fully functional community economic ecosystem is an evolutionary one. This evolutionary process adds value to middlemen who aggregate their collective active capital and confidence towards a single effort to increase the chances of success – increasing both capital and confidence, as well as community sustainability – through learning feedback loops for future efforts across the ecosystem.

These three activities interact in dynamic ways providing feedback, positive and negative, to the community economic ecosystem over time and form the Five C’s of Community Economic Ecosystem Upbuilding: (1) concept; (2) context; (3) core; (4) capital; and (5) confidence. The Five C’s are categorized by their upbuilding function.

The middlemen interact with one another in continuously dynamic ways allowing concept and context to change over time, based on internal or external factors. Likewise, components of the institutional core can and do change over time, as entities, individuals, and institutions change. Furthermore, capital and confidence can change – sometimes growing and sometimes shrinking. Nevertheless, committed middlemen – through successes and failures – continue to pursue collectivist visions and activities, often within community enclaves. These institution-building middlemen when driven by the Five C’s evolve over time seeking to increase their community’s economic fitness across the three broad functions of upbuilding.

Part 3. RACIAL ECONOMIC EQUITY BY DESIGN: 4 Pillars of Sustainable Inclusive Entrepreneurial Development

Undertaken collectively, cooperatively, and consistently, these four broad complementary strategies have the potential to provide the groundwork for an entrepreneurial and business ecosystem evolution that prevents black-owned firms in America from ultimately becoming extinct. The most important aspect is to normalize both black business inclusion and success, and expand its relevance beyond diversity and inclusion cycles, into the national culture of America. A sustained and significant Congressional commitment to invest in these strategies post-COVID-19, would begin this important effort.

The composition of the current inequitable landscape did not happen overnight, but instead from the culmination of more than four centuries of social and economic oppression, exclusion, and suppression. As a consequence, racial equity and systemic cultural change and practice across the business landscape will not come overnight. However, the most effective process to permanent transformation is to identify key metrics that will serve as the foundation of this aspirational and ambitious national cultural change, and intently, attentively, diligently, and watchfully track them.

“To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardship.”

WEB DuBois, Strivings of the Negro People, 1897