The Moment

On Thursday, June 15, 2017, in Durham, North Carolina, more than 300 people gathered inside a modest community sanctuary during the early evening to discuss the future of local economic development. The event was being hosted by the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People, a civic and political organization founded in 1935 for the betterment of the local black community. This assemblage included a diverse population of local public officials, political candidates, elected officials, citizens and residents. The diversity of those in attendance included race/ethnicity, gender, income, education, age, local neighborhood, place of origin, and general background. The attendees in the room, however, did not provide the only diverse context of the event. At least three additional aspects would contextually frame the evening’s conversation.

First, the gathering was being presented as part of the local Juneteenth series of events. Juneteenth is the annual holiday celebrated by some communities to commemorate the date when the last American slaves learned of their independence on June 19, 1865. President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, but it took more than two years for the news of freedom to reach blacks in Texas. Durham holds annual events during the week of Juneteenth.

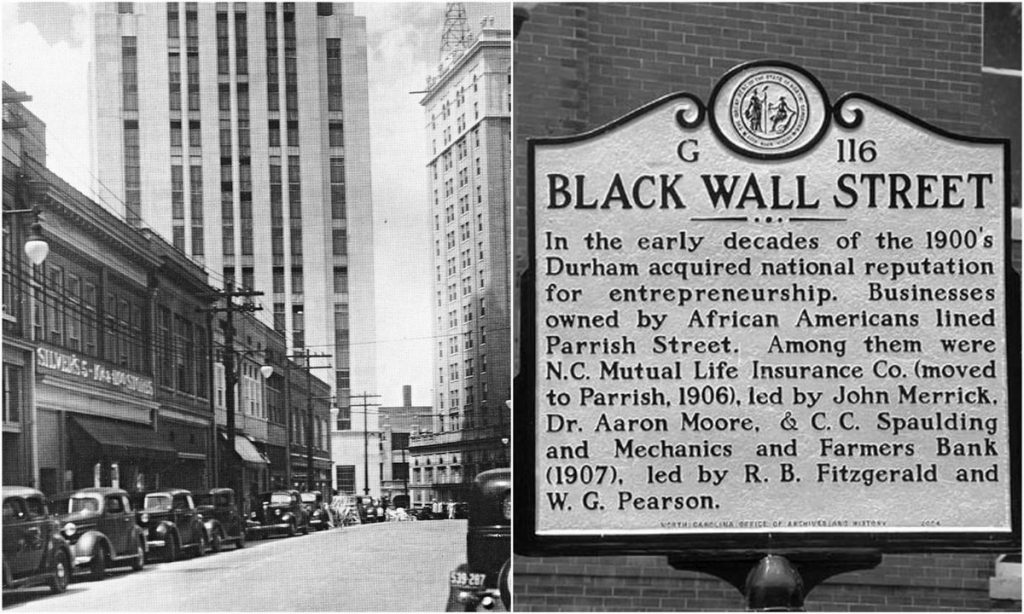

Next, the location of the event was historically significant. The event was being held in the sanctuary of the Hayti Heritage Center, a cornerstone of the once bustling Hayti District. The name “Hayti” referred to Durham’s historically black community renowned for its robust black entrepreneurialism in the century following slavery. At various times during this period, Durham became alternatively known as “the capital of the Black Middle Class,” “the City on the Hill for Blacks,” “Black Wall Street,” location of the most African-American millionaires per capita in the United States, and home to hundreds of black businesses, including the largest black-owned business in the world. However, in June 2017, the Hayti District was not even a shell of itself. Partly because of broader economic trends following social integration, the construction of a highway through the heart of the district, and global economic forces, Hayti was no longer a social and economic marvel. An area once home to numerous keystone institutions had very few remaining community anchors. The Hayti Heritage Center was one of those few remaining institutions from the prior century – actually, the nineteenth century. However, it could no longer be considered a keystone.

Finally, the gathering was presented as a moderated discussion about the next phase of economic development and investment in Durham. If an American-Tobacco-anchored downtown and a robust black entrepreneurial ecosystem had been economic cornerstones of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Durham, both had crumbled by the end of that century. However, since the beginning of the new century, significant capital investments had provided a second life for the downtown. Additional capital supported economic development growth in other areas of Durham, specifically in the northern and southern geographies. South Square, Northpoint, New Hope Commons, and Southpoint, were all new or upgraded development projects consisting of various mixes of retail, residential, and commercial anchors. Still, no area saw the type of public and private capital investment as did downtown Durham, estimated at over $1.2 billion. The return on investment had been significant. Durham was now being mentioned alongside entrepreneurial hubs like Austin, Boston, San Francisco, and even Silicon Valley. Some rankings placed it as the best place in America for entrepreneurship.

While northern, southern, and downtown Durham had each received significant capital investments for economic development, east Durham had received virtually none. East Durham was the historically black and low-income area, which had seen little change in the previous decade of surrounding growth, except that it had become browner and poorer. But because of that surrounding growth, gentrification was now becoming a reality. Areas once the exclusive domain of only the poorest citizens of the community were now being purchased for hundreds of thousands of dollars; primarily by those relocating from northern or western states. The lack of affordable housing in Durham, as well as the demographics of who should benefit from any such efforts, were central themes of the night. With thousands of new residents moving to Durham annually, many of them educated and white, the central questions were who the next phase of Durham would be built for, who would benefit, and who would be left behind? In short, the question of the night was who would the future of Durham belong to?

The Movement

The title of the Hayti event was “Building a Durham Economy that Works for All.” Over the course of 2.5 hours, the moderated conversation advanced sequentially across three discussions – covering Durham’s economic past, present, and potential future.

Discussion #1: The Past

The Past: For some, learning about the past, particularly the rise of Durham’s Black Wall Street in the midst of the segregated Jim Crow south, was a source of great fascination, pride and joy. For others, the eventual decline and decay of the Hayti District evoked sorrow, pain and ultimately, anger. Many of the African-Americans, when hearing about (or recalling) the freeway construction that leveled Hayti nearly six decades prior, and its intentionality, expressed sentiments of anger at what the community had lost, and under what circumstances. At times, all these emotions seemed simultaneously present in the room. Whatever the past state of Durham, it was no longer a black mecca of economic progress or prosperity.

Discussion #2: The Present

The Present: Referencing the most recent United States Census Survey of Business Owners (SBO) data, and other community indicators, many in attendance at Hayti seemed surprised at Durham’s current economic and social conditions. Among the most shocking findings from the data was that Durham’s black entrepreneurial population had grown much slower than other major cities in North Carolina, and the state overall. From 2007 to 2012, black entrepreneurship in North Carolina and the United States had increased by over 34 percent, but only 14 percent in Durham. More surprising, not only did Durham rank lower than major metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) like Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem, among others, in black entrepreneurial growth, but also lower than the much smaller, and more rural, community of Rocky Mount. Furthermore, though Durham’s black and white populations were essentially equal numerically, blacks while significantly underrepresented in business, were significantly overrepresented in poverty. For a city that professed a desire to be the most diverse entrepreneurial hub in the world, and aspired to work equally for all, these facts challenged Durham’s core belief of itself – as an equitable community.

Discussion #3: The Future

The Future: If the “past” and “present” discussions created the most dissention in the sanctuary, as attendees sought to assign fault and blame for the current state of black Durham, the “future” discussion created the most bewilderment. Though eight distinguished panelists representing the public, private, philanthropic, academic, and community sectors shared their insights and knowledge, none offered definitive solutions to the locally identified challenges. Even the most vocal audience members appeared at a loss about how to reverse Durham’s inequitable trends. Imagining an economy that worked for all appeared easier than designing one. Nearly everyone in the room that evening agreed that Durham’s economic development ecosystem was not functioning for all. But no one seemed able to offer concrete solutions. For many, there seemed to be broader forces at work that the community could only hope to slow, but not stop completely. The oldest members of the audience, and many blacks who knew its history, were nostalgic for Hayti of the segregated era.

The seed of that discussion laid the groundwork in earnest for the modern “Durham Global Equity Project” (DGEP) effort.